Guest post by Dr. Scott Nichols

Dietitians face an unenviably daunting task when asked to describe the differences between wild and farmed fish. Your conundrum is how to distill an ocean of information into something useful without leaving something important on the sidelines. Perhaps you can meet the lion’s share of interest by addressing an overarching question: Does farming meaningfully change a fish’s healthfulness? Let’s divide that into two questions. Firstly, are farmed fish nutritionally distinct from wild fish? Secondly, are there differences between farmed and wild fish in the potential toxins they may carry?

Are Farmed Fish Nutritionally Different from Wild Fish?

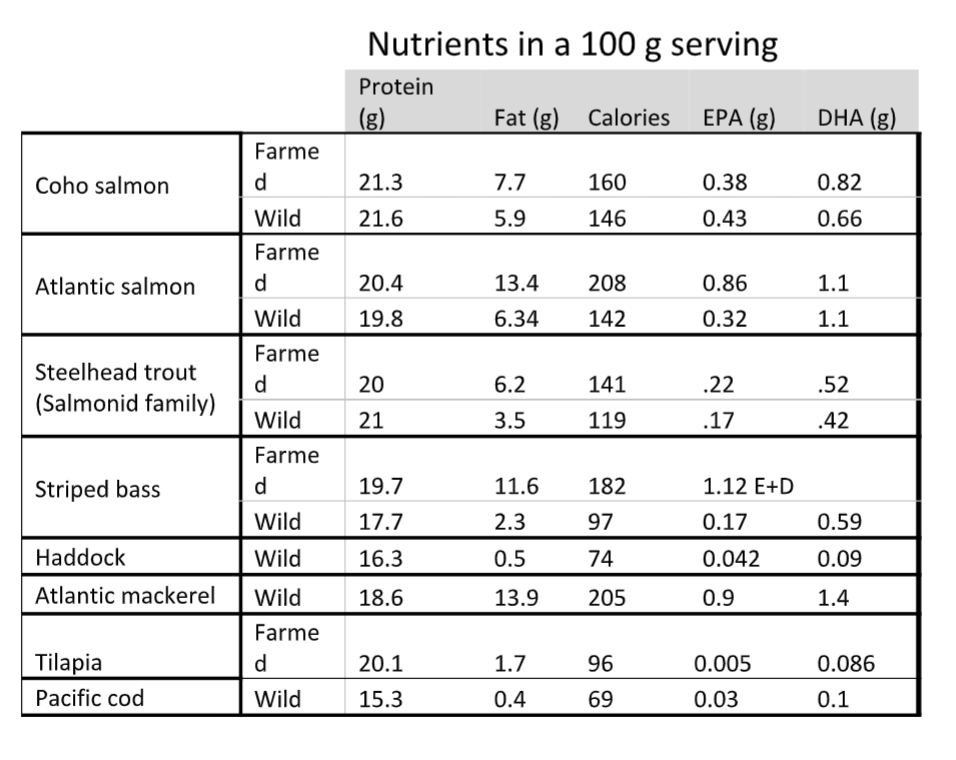

The table below shows macronutrient compositions of wild and farmed fish of the same species are largely similar. Protein content varies little. More variable is the difference in fat content. This reflects fish feeds having higher fat content than the diets of wild fish. The essential omega-3 fatty acids vary a small bit between farmed and wild, with – on average – omega-3s being slightly higher in the farmed

fish. More prominent differences arise between species. Here, you see differences in fat content and, notably, in the levels of the essential omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA. Our focus more properly rests on the differences between species rather than those found between farmed and wild for a given species.

Toxins in Fish

Among the most studied cases of toxins in fish is with a class of compounds called persistent organic pollutants (POPs). POPs include PCBs and dioxins, both of which are carcinogenic and neurotoxic, which caused the U.S. to ban them in 1978. Sadly they are quite stable compounds and, through both use and disposal, they continue to reside in bodies of water.

Particularly with salmon, POP contaminants have been the focus of scientific attention for two decades. Scrutiny began with a 2004 scientific article that showed some farmed salmon had higher POPs than wild salmon. The cause was feed ingredients in salmon diets. Fortunately, salmon diets have changed radically over the past two decades. Scientific follow-up studies show farmed salmon progressed to the point where they have less POP than wild-caught (see here and here).

All this needs to be in perspective though. Farmed and wild salmon alike are well below the levels FDA

says cause concern.

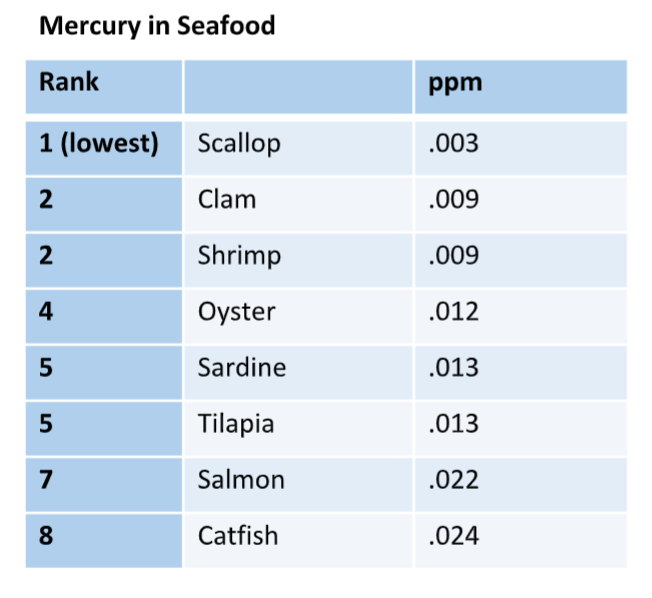

Another well-studied area is the presence of mercury in many species of seafood. Mercury, largely from industrial sources, is both an air and a water pollutant. It occurs in both plants and animals and that includes seafood. The first thing to say is that mercury is generally present at low levels in most seafood. And, in the chart below you see that seven of the eight lowest mercury levels in seafood occur with

farmed species (sardines are wild captured; salmon is a mix of farmed and wild, and the remaining six are mainly farmed).

What looms largest though is the effect that mercury may have on us. In one of the most sensitive areas, namely children’s neurocognitive development, a recent scientific study of 103,000 mother/child pairs found when mothers ate seafood during their pregnancies their children had an average 7.7 IQ point increase compared to kids of moms who ate no seafood. Moreover, there were no adverse effects on kids whose moms ate even up to 100 ounces of seafood per week. The key takeaway from this work is that eating fish offers tangible benefits and avoiding fish has detriments we must seek to avoid. Let’s circle back to where we started above. For fish of a given species, nutritional differences between farmed and wild-caught don’t leap off the page to compel your attention. Much more meaningful differences occur between species. Concerning toxins, they exist in seafood because they exist in our environment. Farming doesn’t seem to exacerbate their accumulation. Rather, the species with the least toxins are largely farmed (with a big tip

of the hat to shellfish). So then, what should capture our attention? Throughout many pages at the Seafood Nutrition Partnership (here for instance) and elsewhere there are stunning examples of how beneficial seafood consumption is for countermanding diabetes,

improving cardiac health, brain development and childhood neurocognitive development. Eating seafood is one of the most health-promoting things we can do for ourselves. And yeah, it tastes better than just about anything else you might want to eat.

Leave a Reply